Short stories

Princess Nirgidma

Ubashi’s Concubine

A Journey In Inner-Mongolia

Princess Nirgidma (prelude to The Mandate)

Carl Barkman

Who was Nirgidma, to whom I dedicated my novel Asaray, a Russian translation of which (entitled Nakaz Bogov) is now being published in Elista, the capital of Kalmykia? I shall try here to describe her extraordinary personality and her interesting life.

When I first met Nirgidma in Peking (Beijing)) in 1947, I was immediately impressed by that remarkable lady. Although she was a princess of the Torghuts, a nomadic people in Central Asia, she spoke beautiful French and very good English, Chinese and Russian.

She had received a western and Chinese education at the French nuns’ school Sacré Cœur in Peking and studied a wide range of subjects in Paris and Brussels, among which political science, literature and music. Her husband, a French diplomat, Michel Bréal, was consul-general in the former Chinese capital, where I represented the Netherlands. Among the diplomatic wives she stood out as an amazing polyglot and an authority on culture, both oriental and western.

She was forty years of age then, but looked much younger. A slender, charming young woman, whose face reflected a serenity which suddenly could change into a lively interest. An oriental beauty? Yes, but also western, for her clothes, gestures, and subjects of conversation were western, in particular French. When she discovered my interest in the history of her nation, which I had studied in my university days, we often spoke about Central Asia in general, and her people, the Torghuts, especially.

Her early youth had been spent in tents, in the encampments of her nomadic people, one of the largest tribes of the Oirat-Mongols. In the far north-western province of Sinkiang (Xinjiang) they roamed from one pasture to the next. They had a wonderful time there with their flocks of horses, camels and sheep amidst the most marvellous scenery. The summer was spent in the green highlands and Alpine pastures of the Heavenly Mountains and the Altai, in the winter they stayed in the warmer valleys and oases with their subtropical vegetation. But life could be very hard for them too, in times of extreme heat and drought or of unbearable cold.

I became fascinated by the many-faceted history of this far-flung family and decided to devote some further research to it. It took me to Kalmykia, an autonomous Buddhist republic in the Russian Federation, to the south of France, where Nirgidma’s son lives, to a book by a Danish explorer and, last but not least, to old copies of that marvelous monthly, the National Geographic Magazine.

Who was Nirgidma’s father? Prince Palta was a man of great culture, both Chinese and Oirat-Mongolian, a statesman with a thorough grasp of military science which he had studied in Tokyo in the years 1906–1908. Nirgidma was born there. Back in China, Palta became governor of the vast Altai region. In 1917, when Nirgidma was ten years old, her father moved to Peking to take up his post as senator of the Chinese Republic. Already as a young man he had astonished Chinese scholars by his profound knowledge of Chinese history and literature. He also knew English and Japanese well. The famous Finnish orientalist G. Ramsted was greatly impressed by young Palta when during a visit to the estate of his father, Prince Bayar, they talked about such diverse subjects as Buddhist philosophy, and the mutual influence of western and oriental culture in the future.

Palta, who believed that a person’s greatest riches were his intellect, erudition and knowledge, wanted his four children to receive both an oriental and a western education, thus including elements of a Eurasian nature. In 1915, at his request, Tsar Nicholas II granted his eldest son, Mindzhur-Dordzhi, admission to the Russian officers’ school for the nobility in St. Petersburg. When this son returned to Peking three years later, he was initially considered by some as a Russophile, but after his father’s death inherited his titles, and dedicated himself to the task of increasing the well-being of his people. In 1949, after the Guomintang was defeated, he fled with his family to Tibet, and thence to India, from where he emigrated to Taiwan. He briefly served as a member of parliament there and died in 1975.

His sister Nirgidma, following her father’s wish, went to Europe for her university studies. When this princess, then a ravishing beauty, arrived in Paris, she created a furore there, particularly among the intelligentsia of the oirat-kalmyk emigrants. They dedicated poems to her, admired her, fell in love. One of them wrote that her high spirituality and boundless soul’s delight were in evidence whenever she met her compatriots from Russia. And another, Prince Nicolai Tundutov, wrote in a letter to the kalmyk historian and journalist Ilishkin: “Are you interested in Princess Nirgidma? The mention of that name brought memories of years long-past. There are in one’s life encounters which leave an indelible memory in one’s subconscious. With her sharp mind, her wide range of culture, charming manners and incredible warmth, the princess easily won the hearts of men. Just like many others I became enchanted by this amazing woman.”

While studying in Paris, she kept the Torghut Khan, Seng Chen, and her brother, who ruled the eastern wing of the Torghuts in Khara Ossun, informed of political and other developments in Europe. She never mentioned this to me, but when her brother was visiting Peking, he told me how welcome her reports had always been to them, who lived in isolation in Central Asia.

Nirgidma and her elder brother Mindzhur-Dordzhi were children of Prince Palta and his first, Torghut wife Orloma. His second wife, a Khoshut, gave him a daughter, Sertso, and a son, Tsedn-Dordzhi. Sertso, a very talented girl, who apart from Mongol and Chinese, soon mastered English, French and Japanese, died when seventeen years old.

In line with Prince Palta’s ideas about giving a different western education to each of his children, Tsedn-Dordzhi was sent to Germany for his higher learning, whence he returned in the beginning of the second world war to teach German at the catholic university of Peking. In his book Flaneur im alten Peking (Lounger in old Peking), he writes, under his Chinese name of Ce Shaozhen, that his sister Nirgidma, as the wife of the French Consul-General in Peking, was able to provide him and his mother with the means to return to that city from Chungking. As its title indicates, the book gives some rather superficial, though occasionally amusing glimpses of the old Peking, and one gets the impression that the author was a bit of a playboy. Tsedn-Dordzhi’s daughter Devu Nimbo studied in the U.S.A., married an American of oirat-kalmyk origin, and has two children. Her brother lives in Taipei and has become a Chinese author, calling himself Min Huk Hueay.

When during our talks in Peking I told Nirgidma that in my student days I had written an article about the trek of the Torghuts from Russia to China and had translated passages from the official Ch’ing annals about their reception by the Emperor, she wanted to read the article and so I translated parts of it from Dutch into English for her. She helped me with some of the names, and this article was later published in Hong Kong by the university there. Her people and some allied Oirat tribes had migrated from Central Asia to the Volga region in the early 17th century. When the pressure of Russian expansion became too strong, about three quarters of them went back to Central Asia in 1771. Much had been written about this event, especially in Russian, but I appeared to be the only one who had studied the Chinese sources and described their reception in China. This episode, which was new to Nirgidma, fascinated her.

The Oirat-Mongols are of a tolerant and peaceful nature. She was not at all anti-Chinese, although her people had been badly treated by them. In 1932, the Danish explorer Henning Haslund Christensen writes in his book Men and Gods in Mongolia (London, 1935), he received the following information through Princess Nirgidma:

“A movement or revolt against the Chinese provincial government had arisen among the Mohammedan population of Sinkiang. The Chinese Governor invited [the Torghut Khan] Seng Chen to Urumchi in order, as he pretended, to discuss with him the suppression of the revolt. Seng Chen arrived surrounded by his most powerful chiefs, but no discussion ever took place. For after the first day’s banquet, as the Torghuts sat drinking tea in the Governor’s yamen, he had all of the guests shot from behind by his servants.”

For this book by Haslund, Nirgidma wrote a Foreword, in which she says that when meeting him she “enjoyed the pleasure, seldom vouchsafed to us Mongols, of talking freely and unconstrainedly about our country. There was nothing for me to tell him or explain to him, for he was one of us.”

How had they met? Haslund had participated in a Central Asian expedition by Sven Hedin, had lived for years among the Khalka Mongols and the Torghuts. When he was on his way back to Europe, Torghut friends accompanied him on his way to the Russian border. “One day we were overtaken by twenty galloping Torghuts. They were lusty youths on spirited horses wild with the delight of speed across limitless steppes. They checked their course for a while to exchange gay greetings and inquisitive questions, and though we had never seen one another before we were soon like old acquaintances. […] They were Torghuts from Khara Ossun on their way to meet their princess.”

When they had galloped away, “What was all this about a princess”, I asked Lyrup. Did I not know? Nirgitma of the Torghuts was expected back on the steppes from the land of the Franks.

“Nirgitma of the Torghuts, that was of course her whom Seng Chen had so often quoted and of whom I had heard in the tents so many unbelievable things that I had come to regard as a figment of the imagination, the Mongolian girl who spoke the languages of the West and whose qualities had made her a legendary figure on the steppes.

“The same evening we came, dripping with sweat and dusty, to the frontier town of Chugochak where I was to experience a marvellous encounter. She, Nirgitma of the Torghuts, was a slender young woman, whose exquisite Parisian clothes looked exotic against her dark Mongolian beauty. It was only two days since she had left the wagon-lit that she had boarded in Brussels, and her speech and bearing had been formed by seven years of university study and life in European capitals. As many years of nomadic life lay behind me.

“And so it came about that we sat there giving one another widely separated impressions from East and West. […] Our environment was the sun-drenched courtyard of an Asian sarai with horses, asses, camels and caravan people coming and going.

“She had a complete and elegant command of the speech of western culture and to all my questions she had apt answers. For fourteen hours we talked, and, as the hours went by, her speech slipped more and more into Mongolian lines of thought. When we separated to go to the starting-places of our respective caravans […] our farewell words were spoken in Mongolian.” Such were the Danish explorer Haslund’s impressions. We also have an account and photographs by an American author.

In his accompanying article the National Geographic editor writes:

“During our stay [in Urumchi] he [Georges Le Fèvre, the Expedition historian] and I had a delightful discussion with a Mongol princess. She wore riding boots, a tight blue skirt, and a simple white blouse, lightly touched with coral embroidery. Her hair was slightly dishevelled by her dashing ride on a tough-mouthed pony. Attractive, intelligent, objective, this oriental woman spoke French without accent and Anglo-American English seasoned with slang. Dancing with her had seemed strange. Talking with her seemed utterly natural.

“Why do occidentals and orientals dislike one another?”we asked, our actual relationship belying our thesis.[…]

“Why call conservatism dislike?” she replied. “Do you always welcome strangers to your clubs and homes? The oriental has his psychological Great Wall, whose protection is beginning to seem less sure. The man behind it doesn’t want to be loved or even appreciated. He wants to be undisturbed.

“People seek to protect not only property, but modes of life. Perhaps your way of life is right for you, but it threatens ours.

“You are in a hurry and hence barbaric. You are entranced by mechanical toys, which you haven’t mastered. You like frankness; but, until real understanding exists, even formal politeness helps. You dominate world ideals, which differ from ours.”

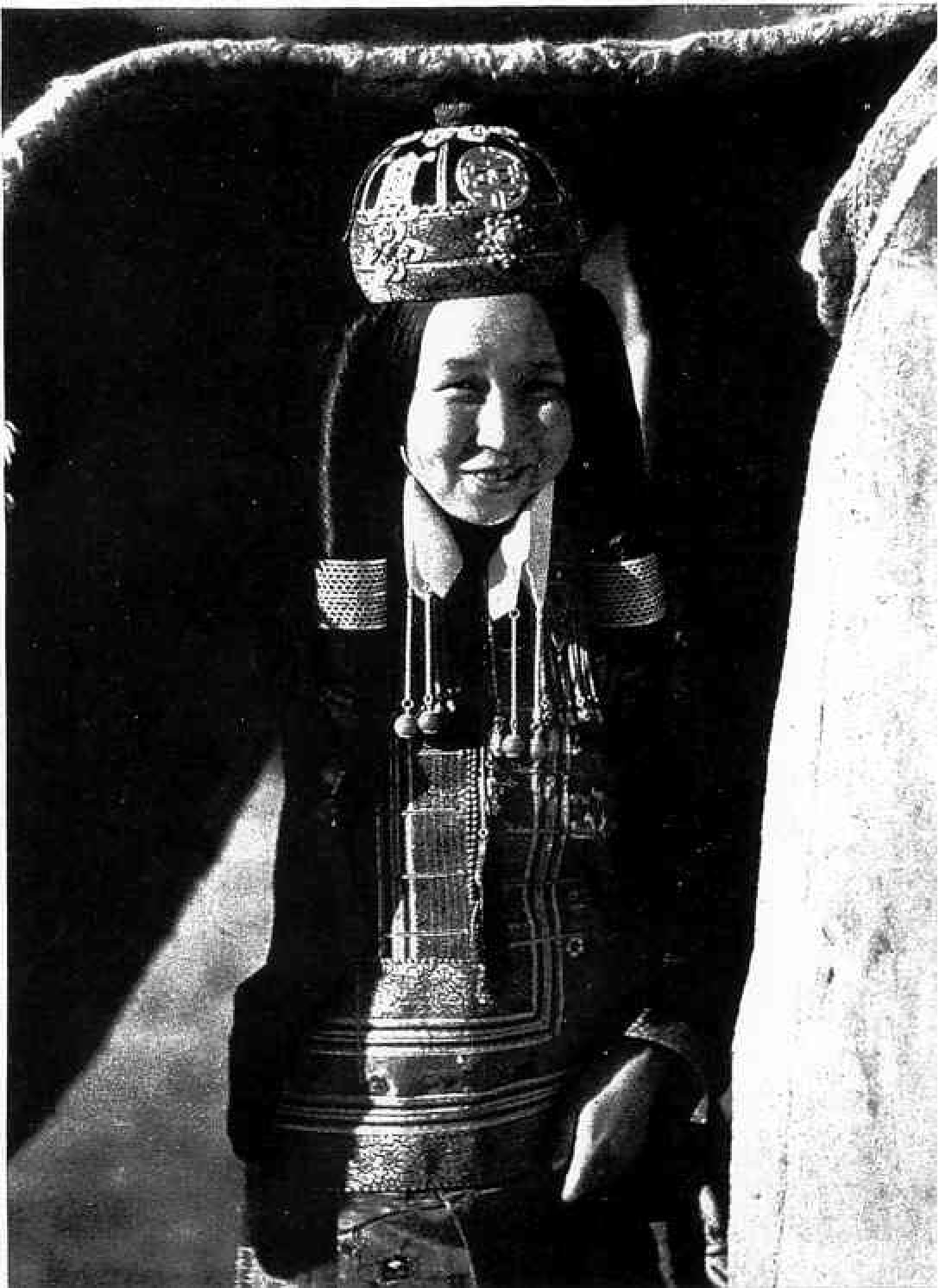

The National Geographic editor and photographer also took a black-and-white picture of her (op.cit.):

“You are men of auto, railway, radio [Nirgidma continued]. You find this a backward land, without roads, speed, a free press, a balanced budget, sanitation, or familiar forms of justice. Hence you pity the Chinese. But they live in the Celestial Kingdom, the center of all the world that counts. Your progress is chaotic, at least in its impact on orientals, because its spiritual values are not realized. We Mongols are emancipated. ‘A good horse and a wide plain under God’s heaven’, that’s our desire. And we realize it.

“My uncle is Shaliva Gegen, third Buddhist dignitary. One simply can’t shock him; he’s too deeply rooted in righteousness. He doesn’t know any great Westerners, even by name; but he said to me, ‘The spark of creative life now exists in the Occident. The Westerners will find the light. But it is still hidden under the husk of materialism. In a future incarnation, the Pantshen Lama will be a Nordic.”

Such were her views when she met the American writer in the thirties. They were more cosmopolitan when I knew her in Peking some fifteen ears later. Her praises risk becoming monotonous, but I have it on the authority of many colleagues and my own observation, that when married to a French diplomat, she was an excellent hostess, who radiated charm and authority, a learned, culturally interested woman, who learned Persian in Kabul, and Arabic somewhere else. Michel Bréal served as Ambassador in Afghanistan, Laos and Thailand. She liked music, gardening, and preferred essays to novels.

In the 1970’s a renewed contact with her inspired me to write a novel about the second son of Donduk-Dashi, Khan of the Volga Torghuts, who in the 18th century was taken hostage by the Russian government. When I read about this young Prince Asaray in Russian historical literature, I could at that time not find anything about his life, and wondered how a young, Buddhist-educated oriental prince would react to the splendour of St. Petersburg and its alien culture. For me, he was an ideal character for a novel. Nirgidma, with whom I was corresponding, told me that according to an oral tradition in her family Asaray had made the return journey to China with his people and played an important role there. She urged me to write the book, which I did, in both English and Dutch. It appeared in the Dutch language in 1997 and I dedicated it to her memory. In a Russian translation it is now being published in Kalmykia. Nirgidma never saw the finished novel; she had died in 1983 in Paris.