Short stories

Princess Nirgidma

Ubashi’s Concubine

A Journey In Inner-Mongolia

A Journey In Inner-Mongolia

Carl Barkman

“What you have begun, you must finish, and what you’re looking for, find it!”, with these words and his best wishes my lama friend bade me farewell in Peking (Beijing) in March 1948, when I started on a trip to Inner Mongolia with my French colleague, a sinologist like me. As a young Dutch diplomat (China was my first post) I had the good fortune of heading for half a year the Embassy office in the former northern capital. My district covered the whole North of China, including Inner Mongolia, and so, though we had no national interests there whatever (who had?), I told myself that I was only fulfilling an official duty by visiting that territory…

But sitting on the Baotou-bound train I asked myself what I was looking for on this trip, what my purpose was. Did I have any purpose apart from the journey itself? Perhaps nothing more, I thought, nor less, than to lose myself in the vast, timeless and soundless space of the green grasslands, and to learn something about those nomads who were forever trekking through the steppe with their flocks, their horses and camels. My companion, Georges Perruche, was a tall, quiet, intelligent Frenchman with a great sense of humour and an endless reservoir of risky jokes, which in any case saved me from ‘losing myself’ altogether in the vast, etc. space. Like me, Georges had long been interested in the Mongols and read a lot about them.

Soon the imposing Great Chinese Wall loomed up, a centuries-old weather-worn bastion rising high from the hills and the ash-grey plain. Space seemingly without life, a moonscape, a void without end. The only human beings were a few camel-drivers accompanying a heavily laden caravan. In the background the paleblue mountains, and nearer by a silvery glistening river, later on a single tree here and there, a mud cabin or a walled-in hamlet. The landscape was monotonous but so vast, so grand that it filled us with a lasting impression. It felt as if we found ourselves in prehistoric times. The gently sloping hills rising from the steppe looked like ancient, giant animals which languidly and softly breathing had laid themselves down to sleep.

On the train we met three nice Americans, agricultural experts, also going to Baotou, where they had their own transport, so-called weapons-carriers (large jeeps). We gladly accepted their invitation to join them. Baotou was one of the dullest, poorest places imaginable, only coming to life when a caravan arrived. Grey, mostly mud houses with rectangular fore- or inner courts, some sort of caravanserais. There was very little traffic in the badly or hardly paved streets: some camels and donkeys, a occasional jeep or truck throwing up a cloud of dust.

Our American friends took us in their jeep to Gong Miao, some 120 km. west of Baotou in the valley of the Yellow River. It was the only place where the Chinese government allowed the Mongols to have their own “autonomous” government. After driving only some 30 kilometers, we saw to our surprise a magnificent lama monastery rising from the plain, the Hunterun süme. The buildings stood perpendicular, in the Tibetan style, white with a red upper edge, with flat roofs on which gold-coloured Buddhist symbols were outlined against a sky of the purest blue. Soon we discovered we had in some way passed a national border, for the lamas knew no Chinese, let alone a western language. Now our interpreter came into his own. We were of course offered the ceremonial tea, to enjoy which one needs years of constant training.

The abbot, a frail figure in a red-yellow robe, with the wise eyes of some one who has seen a great deal of suffering, and extremely thin, almost transparent hands, spoke at our request about his faith. As a Buddhist, he was full of compassion about the human lot: “Life is a concatenation of sufferings, of ignorance and incomprehension. We are surrounded by darkness and mutually antagonistic forces. Our suffering is the result of our wordly desire. Who recognizes this, who rejects this desire and world of illusions, who exerts himself to purify his mind and shows compassion for his fellow human beings, he will ultimately be freed from the dark chaos. Enlightenment, the ultimate perfection of the soundless, radiant Void will be his share.” We were impressed. After a long silence Georges asked what he thought of the situation in which his people found itself. We knew it was rather desperate. The Chinese were invading their territories, ploughing their grasslands and lording it over them. The abbot gave a diplomatic answer: “In the world around us people focus mainly on acquiring possessions, material prosperity. As Buddhists we learn that this aspiration is senseless and can only result in misery and destruction. We nomads too, we could become rich, slaves of our desire, but if we did, we’d lose our bond with nature and with the source of time and of creation. This primordial bond many other nations have lost, but we nomads of the steppe still possess it. That is our wealth.”

Gong Miao was a poor village and the “autonomous government” was neither autonomous nor a government, as we learnt from a trip on horseback into the mountains nearby, where we met with the Chahar-Mongol prince. He was a kind man without any power but had at least a beautiful wife with a splendid headdress of turquoise and red coral beads.

The process of signification was in full swing and the decline of this once so powerful and proud people of horsemen seemed unavoidable. The agricultural experts wanted to drive westward to study the possibility of improved irrigation, but that was mostly Chinese territory and Georges and I yearned to see more of Inner Mongolia. Whether it was due to our eloquence or the wine and cheese we had brought, the Americans let themselves be persuaded to turn northward. After crossing a mountain-pass we soon found ourselves on the vast Mongolian plateau which stretches as far as Lake Baikal. Here there was no road anymore, just an immense plain covered with grass waving in the steppe wind and starting to get green in places. In Guyang we parted with the jeep-owners who were going to hunt for antilopes, whilst we got horses here and left with our interpreter for the seat of yet another “banner”. It was wonderful riding these sturdy Mongolan horsed in the wide-open prairies of this early uninhabited country. It was getting very cold, the temperature fell to well under zero Celsius, and a big round moon stood high in the sky when we reached our destination Dong-gong-qi, existing of two small houses and a yurt (ger). We were received very kindly and given a meal of macaroni and mutton. A fire of cow dung made the interior of the tent very hot. We slept very comfortably in our sleeping-bags.

Further north the number of houses and yurts dwindled even more. Horses were roaming the steppe without any supervision, for hours on end there was no human being in sight, but it was a marvelous journey. I began to feel used to these endless grasslands, perhaps even addicted to them. Nor did they seem monotonous any more, perhaps because the absence of a foreground (bushes, houses, tents) was compensated by the immense background, a panorama stretching for miles and miles. And I loved the ever changing skies which were here even more impressive than in my flat, but varied country of Holland, where the clouds often hang lower than here. For that reason perhaps, and also because they were mostly riding on horseback, the Mongol nomads looked less like dwarfs, walking or cycling, heads bent against wind and rain (as in Jacques Brel’s song My flat country, Mon plat pays: “When rain is falling on streets and squares and flower-beds, / on roofs and spires of churches heaven-high /which are the only mountains in this flat country / when under clouds all men are dwarfs…”).

Now the terrain became more stony and one saw occasionally small piles of stones, so-called obo’s, left there by travelers as an offering for an auspicious journey and serving as sign-posts as well. We were leaving the last herds of horses behind, and as for people, we had not seen any for a long time. The further we went, the wilder the scenery became, waste land as at the time of the Creation. We crossed a river, the Chaganawan-gol, still partly covered by ice, and rode on over the upland plain with no sign of human activity wherever one looked. A considerable time had elapsed, when a kind of mirage appeared far ahead. Was if an optical illusion or reality? Then we both saw something like a castle. Only when we got nearer we discovered its real nature: in the middle of nothing, out of the barest ground rose a Tibetan-style ma temple. In this Bogotai-in süme we were again kindly received by the monks and could not refuse to drink the atrocious ceremonial tea. We also recognized the familiar smell – a mixture of incense, mutton fat, sour cream and manure.

Here our jolly, motorized American travel companions joined up with us again.They had followed a different route and had eaten great quantities of antilope meat. Naturally they boasted unashamedly about their hunting adventures. We left our horses with the monks and continued by jeep. Since our guide knew the name of the river we had crossed, we could now orient ourselves with some precision, which reassured the Americans who behind every hill saw Joe Stalin’s cruel face. We went north up to less than twenty miles from the border of Outer Mongolia (the communist People’s Republic). There we turned southeastward, as far as the Aruhotok monastery, whence we continued east-south-east along a genuine road to Bailingmiao (“Monastery of the Thrushes”, as it is called in Chinese; its Mongolian name is Batur-halak süme — “Klooster van de Sterke Poort”).

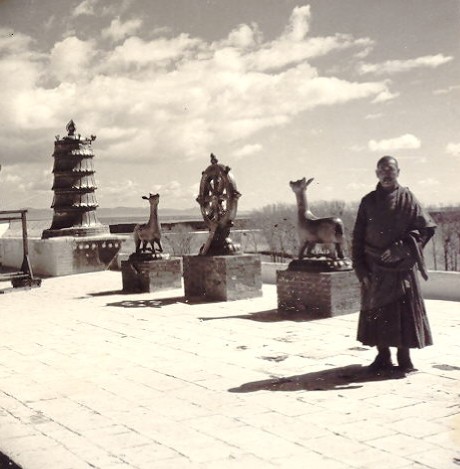

Bailingmiao was the largest and most beautiful lama monastery which we saw on this journey. It was an enormous, impressive complex made up by one big and several smaller temples, courtyards and ger (yurts). In the temple a ger was made ready for us, and we were received here most solemnly by the supreme lama. This monastery was already nearer the zone of Chinese influence: half an hour later the local chief of the Guomintang, followed by the garrison commander came to pay their respects, no doubt also to find out what sort of people these foreign devils were. After a vegetarian meal I tried to meditate for half an hour, something I had never done before, but now I was in a Buddhist monastery after all. It was a strange experience: I felt uplifted, floating, weightless. Some problems with which I had to deal in my life I now saw with great clarity and their solution seemed easy all of a sudden.

Next morning we were awakened by the heavy temple-gong and the deep-melancholy sound of the Tibetan conch-shell horn. While we were brushing our teeth the priests and monks sat in a large circle in the temple square saying their prayers. They were sitting on the ground in long rows facing the main temple whence emerged the abbot and the principal lamas, all dressed in splendid colourful garments, followed by young novices swaying thuribles. The abbot seated himself on a high throne, the high lamas on yellow cushions placed on the ground. After a holy text pronounced by the abbot, which was listened to in dead silence, the monotonous chanting, occasionally rising in volume, and the mumbling of prayers resumed.

At about 20 kilometers north of this Batur-halak süme there is an archaeological site, where Swedish, American and Japanese archeologists and mongolists have made interesting discoveries. I had read some publications on the subject and naturally wanted to visit the place, called Olon-süme, if that were possible. Who would have dreamed that here, in the middle of a desert, ruins existed, not only of a sixteenth century lama temple, built by the Mongol ruler Altan Khan, but also of an early 14th century Roman-Catholic church? Olon-süme-in-tor means, I am told, “ruins of many temples”.

A great number of gravestones were found there bearing the sign of the cross Nestorian Christians had been buried here. After the schism of 431 A.D. large Nestorian communities had been formed in the Middle East, Central Asia and China; they were named after Nestorius, the bishop of Constantinople, who had been condemned in that year by the Council of Ephese on account of his opinion regarding the separation of the divine and the human nature of Christ and his objection against calling Maria “Mother of God”.

It is easy to imagine the excitement of the archæologists when at a later stage they also discovered inscriptions dating from the years 1308 and 1347, which recorded the genealogy of the Mongol royal family of the Ongüt. Why was this such a singularly interesting discovery? In that same period – in 1305 to be precise – the papal envoy, the Franciscan Giovanni da Montecorvino, who was to become the first Roman-Catholic bishop of Peking and “Patriarch of the Orient”, had in a letter to the Pope referred to these Ongüt, Nestorian-christian nomads who lived to the northwest of Khanbaliq (Peking). Montecorvino had visited their territory and reported to the Pope that he had converted their king Georgis, a Nestorian, to the Roman-Catholic religion; that the king – doubtless by force and perhaps by tempting promises – had induced his people to follow his example; and had had a church built of “truly royal grandeur”. The names mentioned by Montecorvino corresponded with those of the inscriptions found here in Olon-süme. And finally the remnants of a building in Gothic style were discovered: it was the Roman-Catholic church built by king Giorgis.

On our further trip southwestwards we visited a Flemish missionary, who was at first confused by this invasion of five westerners and then delighted to receive us and give us a hearty meal. Arriving back in Baotou, Georges and I found two telegrams, he one from his consul-general Michel Bréal and I from Irene, my wife, who informed us that in an unexpected offensive the communist general Nie Rongzhen had cut off the railway near Datong, and that air-traffic to Guisui and Ningxia had been suspended. Michel and Irene had approached the American consul-general and our neighbour Edmund Clubb, who had offered us a ride on a special plane that would pick up in Guisui some American assistant military attachés, who had been hunting in the mountains. We could go by train as far as Guisui, where we stayed the night at the Belgian mission-hospital. Finally, we gratefully boarded the military plane, where we sat on bucket-seats with the American officers and a number of “big horns” (argal) which were indeed enormous, the rams weighing more than ten kilograms and their horns some 170 cm. wide. In Peking we took off our fur-coats. Spring had come here, the grass and trees were green, and the weather was mild. It was good to be home again, but when much later we lived in a big city amidst millions of people, with traffic jams and constant noise, I sometimes went back in my thoughts to Mongolia, where I had found what I then was looking for: the wonderful wide, timeless space of the green steppe and the golden hills, the kind and hospitable nomads forever moving about with their herds and yurts, and the wise serenity of their lama-priests.

Some years ago I visited an interesting exhibition in Leiden of photos taken in Olon-süme! They showed clearly the co-existence there of Buddhist symbols like the lotus and Nestorian-Christian signs of the cross. I then met the explorer who had gathered the material and organized this exhibition, Tjalling Halbertsma. He was an enthusiastic anthropologist with a wide field of knowledge and a special interest in Mongolia. It came as a pleasant surprise to him that I had visited Olon-süme in 1948, and to me that he had recently been there. We met again later, I read his books, and e-mailed to him, when he was back in Inner Mongolia, some of the pictures I took in Bailingmiao, so he could show the monks what their monastery had looked like more than fifty years ago. He published about his various experiences, e.g. in Asian Art Newspaper (May 2003): “Tracing the Gobi — Nestorian Gravestones in Inner Mongolia”.

Tjalling Halbertsma is now international policy advisor to the President of Mongolia.